I contacted fellow bladesmith Myles Mulkey with the idea to collaborate on an Anglo-Saxon seax from around the 9th or 10th century. I wanted to make a pattern welded blade, so I took a four bar core from a failed Norwegian langsax project and welded it to a high carbon edge bar of 1084 steel.

Here are the billets prepared for welding:

To fire weld them, I wire the two billets together tightly and repeatedly heat and hammer them together in small sections.

In the fire:

Once this has been done along the whole length of the proto-blade, I let the it cool to room temperature to relieve stresses built up from the forge welding process.

I then forge the blade closely to shape…

The tang is left short because the material produced this way is hard-earned and precious. Later, an extension of soft wrought iron is welded on.

I grind down to white metal with an angle grinder to analyze the welds.

ground to white steel

After that, I flat grind it with an extremely coarse 36 grit belt.

rough ground

Seaxes are traditionally quite thick knives. We can only speculate exactly what they were used for, but those of this size were most likely used for fighting in addition to daily chores.

the spine is left quite thick

At this point, the blade is ready to be heat treated. This is done by carefully heating to the point where the steel becomes non-magnetic. At this point the iron molecules have austenized, or converted from a “body centered” cube geometry to a “face centered” cube. In this configuration, the carbon atoms can move freely into solution. When rapidly cooled, small hard crystals are formed called “martensite”. This microstructural quality is what makes the blade usable.

the blade is heated to non-magnetic

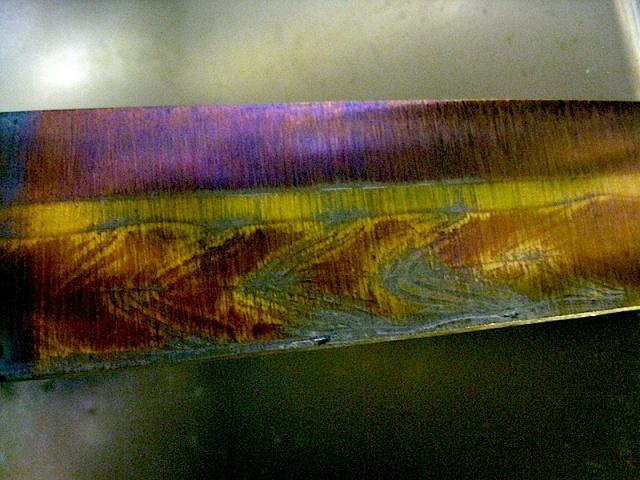

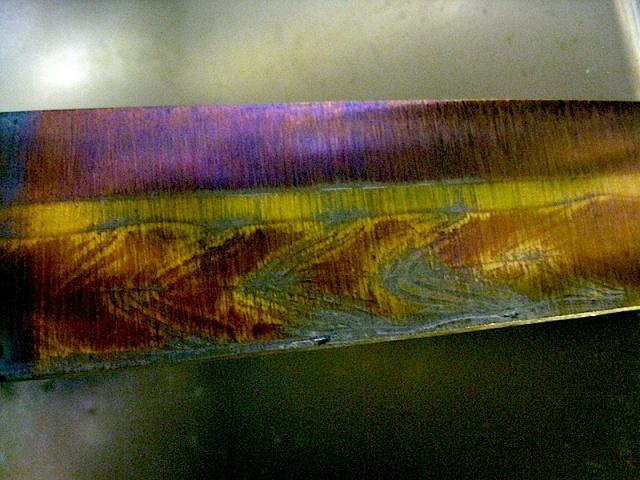

After the blade is quenched in hot oil, I polish a section and temper it at 500 degrees. This slightly softens the blade so that it will not snap or chip out and makes it flexible.

the tempering process produces interesting oxidation colors

The process of polishing is long and tedious, sanding with repeatedly higher grit abrasives. But it is not entirely unenjoyable. I listened to Beowulf, read and translated by Seamus Heaney.

saaaanding….

To reveal the pattern latent in the steel, the seax is immersed in a vertical tube of ferric chloride (FeCl3), a weak acid formed by “killing” hydrochloric acid by dissolving iron in it. Because the blade was welded up of multiple different types of steel, the acid will eat away at the layers at a different rate, creating a topographical effect on the surface.

the etched seax

To accentuate the pattern, high grit sandpaper is used to hit the high spots and emphasize the contrast:

the seax amongst dead leaves

The seax has been sent to Myles to be outfitted with a grip and scabbard, carved with woven Germanic beasts…